PV column

consulting

2025/04/01

“Clean Power 2030” by NESO in U.K.

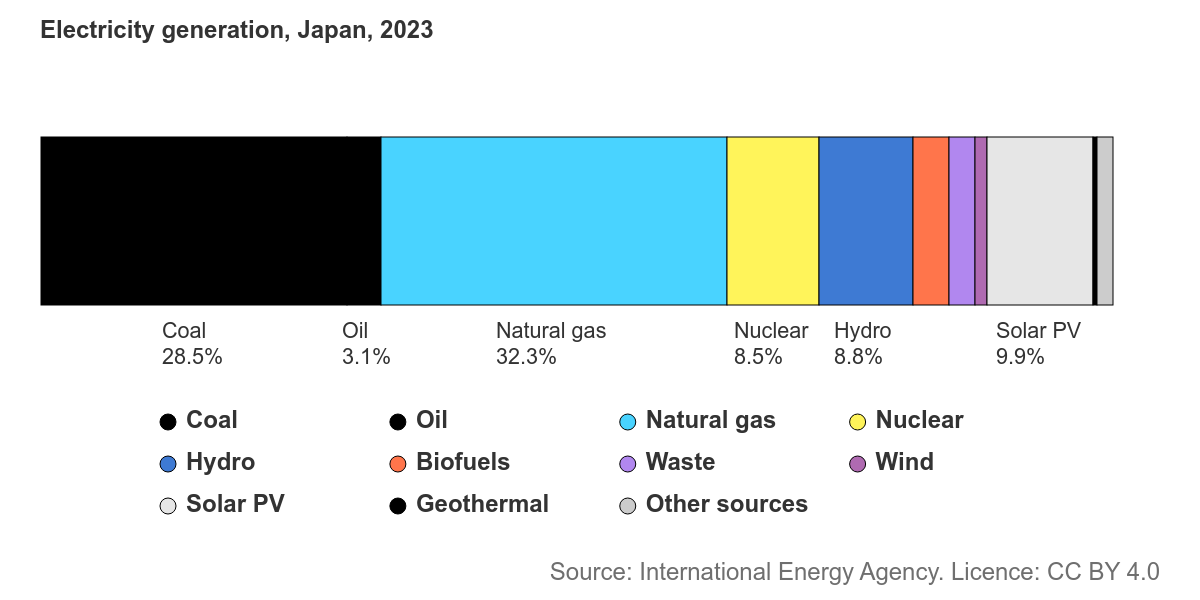

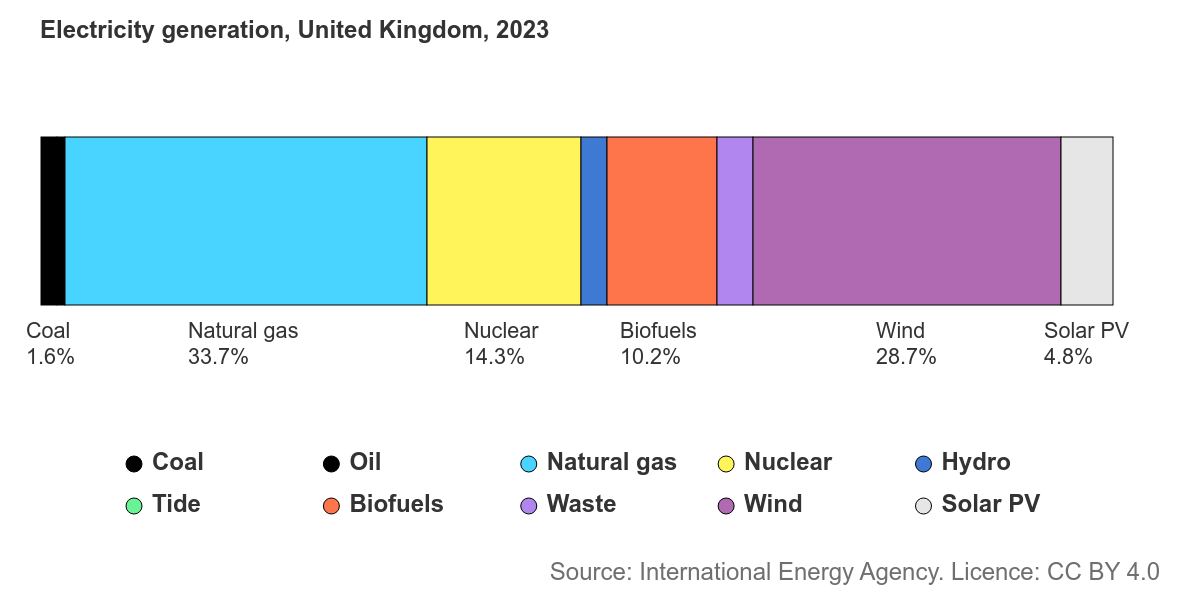

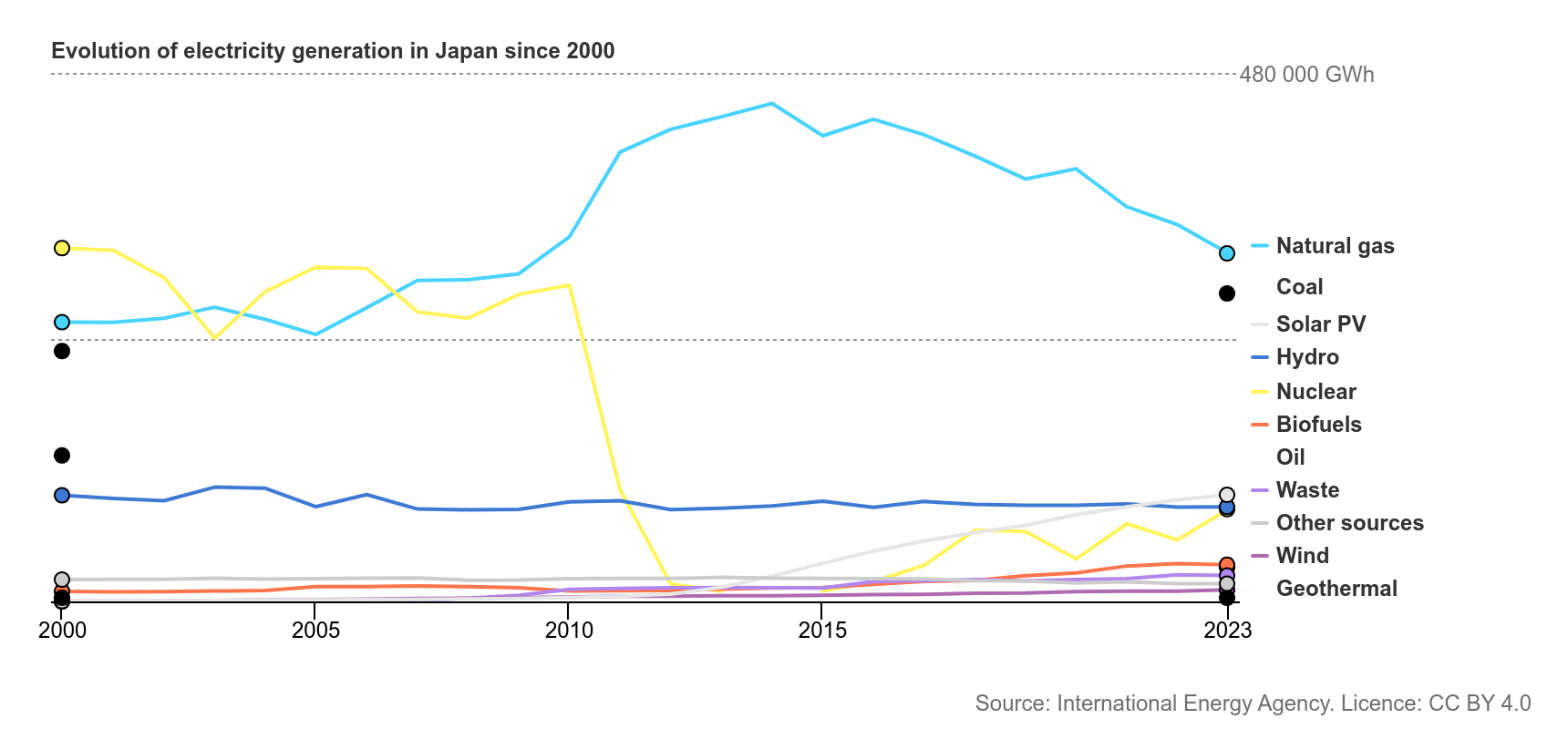

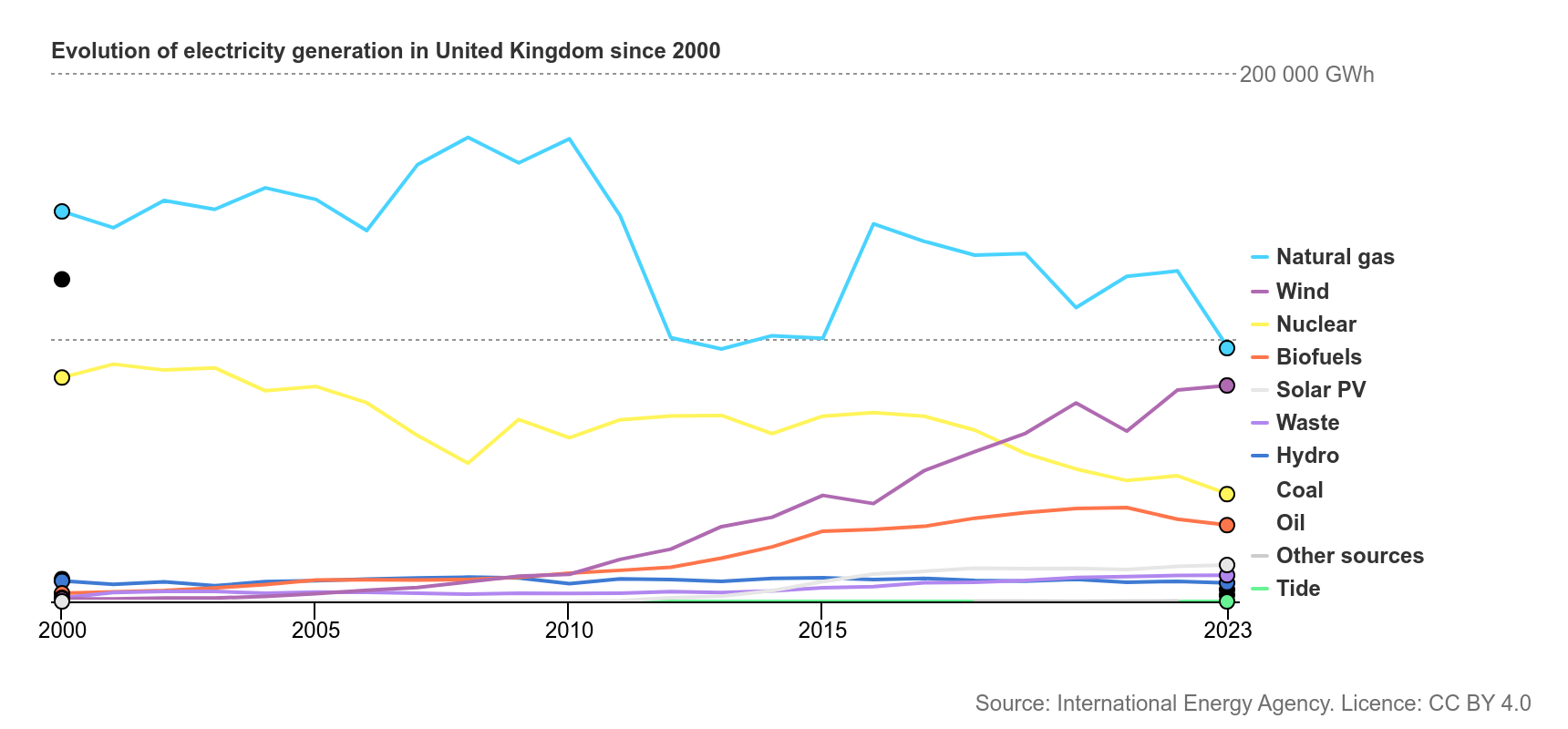

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has published the following information on the composition of power generation sources in 2023 for Japan and the United Kingdom, as island nations, as well as the composition ratio of power generation sources from 2000 to 2023.

Graphs 1 & 2. Electricity generation in 2023 (Japan, UK):

Graphs 3 & 4. Evolution of electricity generation, 2000-2023 (Japan, UK):

The ratios and graphs show that Japan relies heavily on fossil fuel-based thermal power generation (coal, oil, natural gas) at 63.9%, while the UK has made significant progress in introducing wind power (28.7%) and reducing fossil fuel-based thermal power generation (coal, oil, natural gas) (35.3%), indicating that the use of wind power generation and renewable energy has been steadily growing.

In this column, we will introduce the Executive Summary of the report “Clean Power 2030,” published on November 5, 2024 by the National Energy System Operator for Great Britain (NESO), a set of recommendations for achieving the clean power deployment target by 2030.

Source: https://www.neso.energy/news/our-clean-power-2030-advice-government

Report: https://www.neso.energy/document/346651/download

Exchange rate: 1 GBP = 195.00 JPY

**********

The Government’s clean power mission must be about delivery. Clean power by 2030 is a huge challenge that will only be met by doing things differently, by prioritising pace over perfection and by working together across the industry towards a shared vision.

Our analysis, and what we have heard from stakeholders, give us confidence that the step up can be made. The pipeline of projects exists, the necessary network expansion has begun, the system would be secure and operable, and the technologies are available at reasonable cost. It will not be easy, but the foundations are in place.

Reaching clean power by 2030 would restore Great Britain’s access to homegrown resources for electricity generation and support the wider push towards net zero by 2050. It will involve an investment programme averaging £40 billion (JPY7.8 trillion) or more annually, which, with the right policy mix, can be delivered without increasing costs for consumers, without compromising security of supply, and while bringing local economic and job opportunities.

Clean power also enables a compelling offer to consumers to ‘plug in and go green’ and positions Great Britain for the required surge in electric vehicles, heat pumps, electrification of industry and hydrogen production through the 2030s.

Flexibility from both demand and supply will be vital to managing the system and keeping costs down, while offering an opportunity for consumers to engage with the energy system and unlock lower costs for their energy. Data and digital will be key enablers across the whole energy system, but particularly for more efficient use of greater levels of flexibility, to the benefit of consumers.

In this report, we lay out pathways for how Great Britain can reach a clean power system by 2030. Offshore wind must be the bedrock of that system, providing over half of Great Britain’s generation, with onshore wind and solar providing another 29%. New dispatchable low carbon technologies, such as using carbon capture and storage (CCS) or hydrogen, add significant value to the system, with even relatively small levels of operational capacity materially reducing the overall challenge for the rest of the programme.

A major network expansion is needed, in line with published plans for the transmission network and with further strengthening at distribution level. Important projects face multiple barriers, and some are already expected to deliver after 2030. However, they must now be accelerated to deliver by 2030 if the clean power goal is to be achieved. Failure in any single area – generation, flexibility, networks – will lead to failure overall; all parts need to deliver to achieve clean power.

Our pathways imply some choices for the Government and markets to make. Given the scale of the challenge, it may be appropriate to aim high and unblock barriers across all areas, driving through delivery at maximum pace while staying responsive to changing circumstances and new information. Inevitably, some areas will underdeliver, but most investments are low regret, and the risk of over-building is low, given the need to meet growing electricity demand through the 2030s.

A clear plan for clean power, along the lines of the pathways we lay out in this report, can enable a new phase of focused and fast delivery. It should guide decisions on planning, community and public engagement, contracting, grid connections, markets and system operations. With a short and shrinking window of time, pace must be the primary goal. However, this cannot come at the expense of public consent or excessive cost as that would mean the clean power objective would be self-defeating.

An effective plan should give as much visibility as possible to industry, including looking through 2030 to the 2030s and beyond. Clean power is not just a build challenge. The plan should look beyond the infrastructure programme to the supply chain, to operations, including digitalisation, to distribution networks and to the consumer, and beyond power to the rest of the economy.

Our advice reflects a significant programme of analysis and stakeholder engagement, building on previous work such as the Future Energy Scenarios and Pathway to 2030. The next step will be for the Government, reflecting on the advice in this report, to set out its own plan for clean power and then use it to drive delivery. We will use the Government’s plan as the starting point for our Strategic Spatial Energy Plan (SSEP), for the reformed connections queue, and as a guide to the changes we will make as NESO to enable a secure, flexible and efficiently operated clean power system by 2030.

A clean power plan for Great Britain by 2030

A clean power system is one where demand is met by clean sources (mainly renewables), with gas-fired generation used only rarely to ensure security of supply, primarily during sustained periods of low wind. For the analysis in this report, we have described this as: by 2030, clean sources produce at least as much power as Great Britain consumes in total and unabated gas should provide less than 5% of Great Britain’s generation in a typical weather year.*

Our analysis points to the following priorities for successful pathways to clean power:

- Unlock flexibility of demand and supply. Flexibility is vital in a system with more variable renewables. There are large opportunities to increase flexibility in both demand and supply, across residential and commercial applications, and in industry. However, flexibility is not currently valued in full and faces multiple barriers. Markets and processes must be redesigned, and data and digital approaches embraced, enabling infrastructure must be delivered and barriers unblocked.

- Backing offshore wind and renewables. There is no path to clean power without mass deployment of offshore wind, together with onshore wind and solar. Sustained rollout of offshore wind is needed at over double the highest rate ever achieved in Great Britain. Increased rollout will need to continue through the 2030s. Transparent and comprehensive investment signals, contracting arrangements and delivery environment for these projects will be key to the costs and success of the clean power programme as a whole.

- Recognising the value of dispatchable low carbon plants. These play a vital role that is different to weather-dependent and firm low carbon plants in being able to match to demand regardless of conditions. Biomass can shift into this role as can new CCS and hydrogen projects if they can come online by 2030. CCS and hydrogen are also important and currently under-developed technologies for the global transition, implying progress in this area can help lead the global effort. Contracting arrangements should be developed with the expectation that these plants operate flexibly, rather than operating continuously. More will be needed beyond 2030 and will be advantageous if delivered earlier, potentially enabling a lower cost 2030 system that takes pressure off other delivery challenges.

- Delivering network plans in full and faster. Current plans for network expansion are sufficient, but must overcome many barriers to deliver on time, and some vital projects need to be accelerated to deliver by 2030. More than twice as much transmission network needs to be built in the coming five years than the previous ten, along with accompanying enabling works, connections and distribution network strengthening.

- Keeping options open. Our pathways recognise various uncertainties, including on demand and deliverability of certain options. In the face of these uncertainties, and the need to manage delivery risk, there is high value in pursuing multiple options where they exist and encouraging competition between, not just within, different technologies.

The rest of this summary outlines the findings from our analysis and engagement: our pathways, their feasibility, critical enablers of clean power and the benefits and costs.

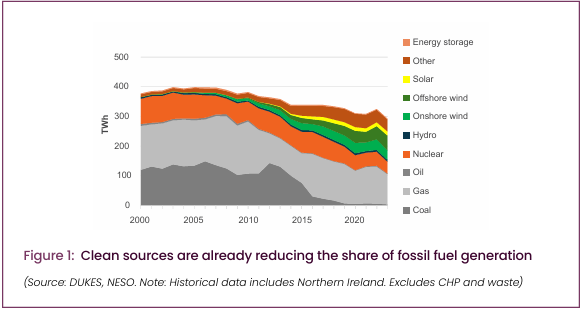

Clean power pathways

As Great Britain has improved efficiency and rolled out renewables, the share of electricity generation from unabated gas (from gas-fired plants not using carbon capture and storage) has fallen to around a third. A further 12% of demand was met by imported power in 2023. Our clean power pathways see Great Britain become a net exporter of power and reduce the share of unabated gas generation to below 5%. All our pathways involve early electrification of heat, transport and industry. A reductionist approach that slows down electrification to lessen the challenge of clean power would undermine the core objectives of cutting energy costs and supporting net zero.

Figure 1. Clean sources are already reducing the share of fossil fuel generation:

Our clean power pathways see a four-to-fivefold increase in demand flexibility (excluding storage heaters), an increase in grid connected battery storage from 5GW to over 22GW, more pumped storage and major expansions in onshore wind (from 14GW to 27GW) and solar (from 15GW to 47GW) along with nuclear plant life extensions.

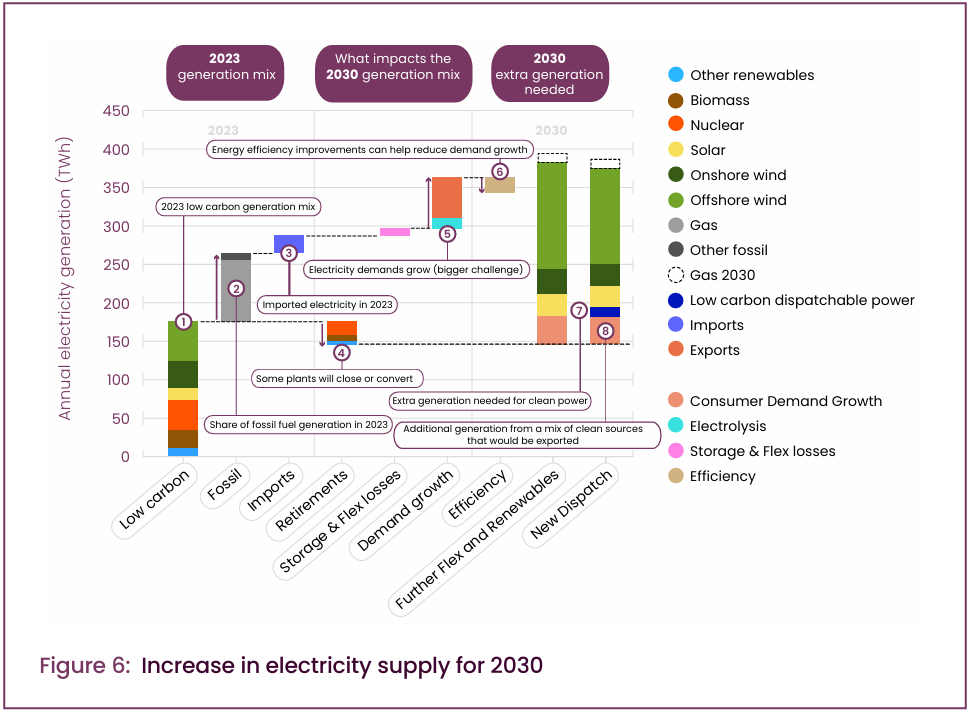

Our work identifies two primary clean power pathways. In addition to the elements outlined above, one pathway successfully builds 50GW of offshore wind by 2030, but no new dispatchable power from hydrogen or gas with CCS. The other pathway delivers new dispatchable plants (totalling 2.7GW) and 43GW offshore wind. Either of these requires a dramatic acceleration in progress compared to anything achieved historically and can only be achieved with a determined focus on pace and a huge collective effort across the industry.

Figure 6. Increase in electricity supply for 2030:

The pathways involve different risks and challenges, both at the portfolio and project levels. Delivering new dispatchable power would reduce supply chain pressures for renewables and bring lower system costs in our analysis. However, new technologies may need more government support initially and would leave some exposure to volatile international gas prices, albeit significantly reduced from today. The higher levels of both offshore wind and dispatchable power will be needed soon after 2030 and progressing both could in parallel bring industrial benefits and new jobs to Great Britain.

Our clean power pathways push the limits of what is feasibly deliverable, but there are some flexibilities at the margin. For example, onshore wind and solar could substitute for offshore wind, more demand side response could substitute for batteries and more hydrogen or CCS could substitute for most other supply options.

A major expansion of the electricity networks is needed alongside to connect and transmit these new power supplies. Operation of the system will need to evolve too, which can be done and will be reflected through our developing plans, which will be updated in our March 2025 Operability Strategy Report to align to the clean power goal.

Feasibility of clean power

Delivering a clean power system by 2030 will be hard, but our analysis and engagement indicates the foundations exist to make it possible. Success will need a combination of efforts across the household, community, regional and national levels.

Historically, customer engagement with energy has been low. However, energy efficiency has improved as lights and appliances become more efficient. Trials of demand flexibility, by us and market participants, demonstrate the untapped potential that can grow with the rollout of new technologies like electric cars alongside smart capabilities and digitalisation. We are already seeing demand side flexibility playing a role in the balancing mechanism, frequency services and distribution network markets.

Key supply-side technologies (e.g. offshore wind, onshore wind, solar, batteries) will all need to deploy more on average each year to 2030 than they have ever done in a single year before. This will inevitably stretch supply chains and require accelerated decision making in planning, permitting and awarding of contracts. But there are enough projects in the pipelines to sustain the required rollout if they can progress to delivery.

CCS and hydrogen are first-of-a-kind projects for Great Britain and previous attempts have not progressed to delivery. The Government has begun awarding funding, which provides a platform for a material contribution by 2030 or soon after. There are developers with specific projects ready to deliver for 2030 under the right conditions.

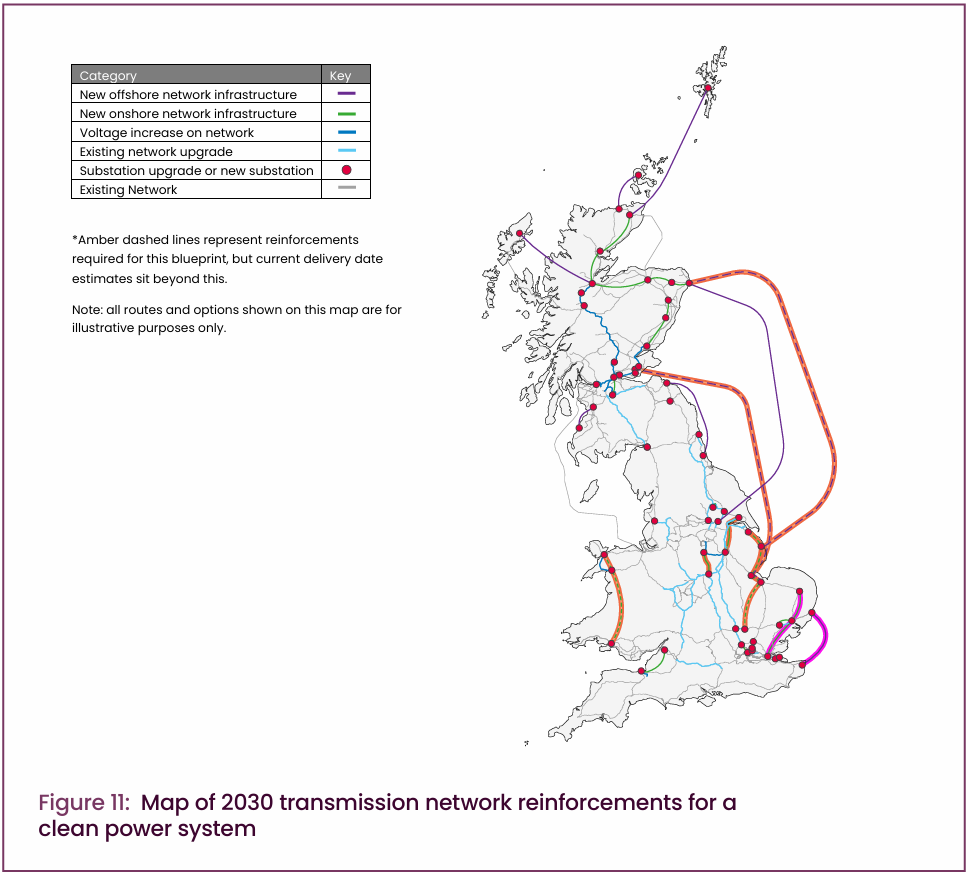

Our clean power pathways require up to £60 billion (JPY11.7 trillion) of network investment cumulatively to 2030, to build nearly 1,000 km of onshore and over 4,500 km of offshore network and accompanying enabling works. That is more than double over five years what has been built in total in the last ten. The industry has begun to mobilise for this challenge, with most projects set out in the ESO Pathway to 2030 network plan underway and aiming for delivery by 2030. A handful of key projects will need to be brought earlier from their current delivery dates of after 2030.

Figure 11. Map of 2030 transmission network reinforcements for a clean power system:

The clean power system must also be a secure system. Our analysis shows that the mix of demand, storage and supply in our clean power pathways can manage the risks associated with balancing supply and demand at the same or better than current levels. This will require that even as use of gas generation drops to very low levels, most of today’s gas plants remain on the system out to 2030 and beyond. Appropriate arrangements will need to be in place to ensure these plants remain open but do not run excessively (such as to provide power for export).

Perhaps the hardest challenge will be delivering across all areas together. Many elements of the supply chain are shared and there are overlaps in the required workforce and skills. Failures in any one area can cascade to failures elsewhere. At the same time, doing things differently, the shift to a mission-led approach, the opportunity for a positive national conversation, the chance to provide greater visibility and confidence and the possibility of resolving challenges at programme rather than project level can bring benefits for all parts of the challenge.

Enablers for clean power

Government has taken initial steps to support their clean power ambition, including lifting planning restrictions for onshore wind in England, increasing the low carbon auction budget, establishing the Clean Power 2030 Unit and funding a range of CCS enabled projects, including power CCS and low carbon hydrogen production that can support hydrogen to power. Continuing this progress to enable clean power by 2030 will require that things are done differently across the delivery chains:

- Markets and investment. Various market arrangements and investment support schemes are in the process of, or will need, reform to reach clean power and operate the system efficiently. Decisions must provide stability and confidence to underpin the large amount of investment required, while supporting innovation and efficient operation of the system. An element of competition will help to keep costs down.

- Planning and consenting. Significant volumes of projects need to pass through the planning system to start construction on rapid timescales, while maintaining community consent which is vital to the mission. Given that construction for many of the required projects needs to begin in the next 6-24 months to be in place by 2030, upcoming planning reforms will need to significantly streamline and speed up processes.

- Connections. The connections queue must be formed of ready-to-connect projects that align with the Government’s plan for clean power by 2030 and once developed, the Strategic Spatial Energy Plan (SSEP) and future iterations. We have begun the process of connections reform and will develop the SSEP based on government’s plan for clean power by 2030.

- Supply chain and workforce. Acute supply chain and workforce challenges must be overcome across nearly all generation, storage and network projects. Policy certainty, visibility of the future market and swift funding decisions are needed to ensure developers can mobilise the supply chains and workforce needed. Over the medium term, greater strategic coordination can enable delivery while supporting the growth of domestic supply chains and a skilled workforce to meet the growing pipeline of projects.

- Digitalisation and innovation. Prioritised and coordinated action is needed across the sector to drive digitalisation and common governance is required for orchestration of a sector-wide digital and data plan. Work has started on a common data sharing infrastructure for the sector, but this needs to be accelerated through policy and incentivising adoption. Accelerated AI adoption and transformative innovation need to be prioritised to align with the government’s plan for clean power by 2030.

- NESO as a partner in delivering clean power. NESO will play a central role in delivering clean power. Putting the government’s plan for clean power by 2030 into operation will require coordinated action across the energy industry and its institutions, with NESO working as a partner with Government, Ofgem and key decision makers. This includes supporting Energy Code Reform, developing our implementation and engagement plans and reviewing our operations to ensure alignment with the plan.

These actions are needed for 2030 and must be implemented alongside actions needed to maintain momentum for the period beyond 2030. Many projects are already in development that will only come to fruition in the 2030s and must collectively deliver continued progress through that decade.

Reaching clean power will have impacts on consumers, communities and businesses across Great Britain. While energy policy is generally a reserved matter, planning and consenting are devolved. Consenting of some projects will require a mix of reserved and devolved competency, requiring coordinated partnership between the UK, Scottish and Welsh governments. Furthermore, devolved policies such as the Scottish Government’s Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan will have implications for reaching clean power and beyond. This report does not go into details of the planning and consenting changes required, but it is clear that close collaboration between the UK and devolved governments will be needed.

Benefits and costs of a clean power system for Great Britain

A clean power system will help meet Britain’s climate targets. It will reduce gross power sector emissions in 2030 to below the level in the Climate Change Committee’s net zero pathways. It will set the system on track for the higher demand growth expected through the 2030s as electrification accelerates and supports that electrification by offering consumers clean power. Being one of the first major economies to decarbonise from a historically fossil fuel-based power system to clean power can form a strong part of the UK’s wider climate leadership.

Clean power can also support wider economic objectives. An investment programme averaging over £40 billion (JPY7.8 trillion) annually can support economic opportunities and new jobs across the UK, and our analysis suggests it can be paid for without increasing costs to consumers, provided the increased pace does not overheat supply chains or otherwise drive up project costs. New networks and an abundant supply of clean power can enable growth in other sectors, including the growing digital and data economy.

This major investment programme should be largely delivered by the private sector and will bring material savings in annual running costs as less gas needs to be bought to provide power. Our analysis in this report suggests that, together, these will lead to overall costs for clean power – the costs that are passed on to consumers – in 2030, that are no higher than they would have been without the shift to clean power.

Great Britain would be much less reliant on energy imports for power and far less exposed to fluctuations in international gas prices. Without accelerated action a repeat of the gas price spike of 2022 would add around £10 billion (JPY1.95 trillion) to electricity system costs in 2030, but would add only £5 billion (JPY975 billion) in a clean power system. Avoided price spikes could be far more significant, noting the very high rises in electricity prices during the recent gas price crisis.

A crucial determinant of overall costs will be the impact of the Government’s new approach to clean power. If it can provide greater visibility and greater confidence, while unblocking barriers and easing delivery, there may be opportunities for costs to fall. Conversely, if supply chains become excessively stretched, costs could escalate.

How costs translate to customers’ electricity bills will depend on policy design and market dynamics that we do not attempt to predict in this report. Additional opportunities exist for bills to fall with energy efficiency (expected to reduce typical household electricity consumption by 5 – 10% to 2030) and as legacy policy costs for early renewable contracts expire.

Policy design should target not just the average electricity user, but the distribution of customers. The benefits of shifting to clean power and electrifying heat and transport should be available to all households and businesses, ensuring a just and affordable transition.

In conclusion, the success of the Government’s clean power mission will be as much about how it is delivered as what it is delivering. Urgency and momentum are critical. A good approach begins with a good plan. There is an opportunity to create a virtuous circle of reduced barriers, increased visibility, easier delivery and lower costs alongside increased pace. As the newly established National Energy System Operator, we look forward to supporting the Government in this challenge.

**********

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank NESO for permission to publish this article and IEA for providing the data.